The man who reached for the sky

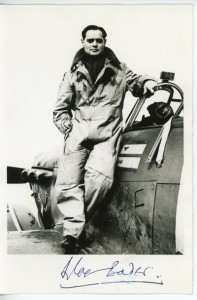

One of the most colourful characters associated with St George’s Hospital is Douglas Bader, the highly decorated fighter ace whose extraordinary life was immortalised in the film Reach for the Sky.

He shot down more than 20 enemy planes, despite losing both legs in an earlier plane crash that threatened to keep him grounded during World War Two.

Demand for experienced pilots gave Bader the change he was waiting for as Europe fell to Nazi Germany’s all conquering armies.

It set the stage for what Winston Churchill described as Britain’s ‘finest hour’ when a heavily outnumbered Royal Air Force doggedly fought off the German Luftwaffe during the summer of 1940.

Bader shot down his first enemy plane and damaged another in a dogfight over the French coast on June 1.

The RAF discounted his belief that attacking from altitude with the sun behind you was a valid strategy although it was used to devastating effect elsewhere.

He also preferred firing at close range arming his plane with heavy low-calibre bullets that could punch fist-shaped holes in the flimsy fuselage of enemy planes.

It called for ice cool nerves in the murderous confusion of aerial combat but Douglas Bader lacked neither courage nor faith in his flying ability.

His talent was evident at an early age when he made his first solo flight after just 11 hours flying time under the terse but experienced tutelage of flying officer ‘Pissy’ Pearson.

Bader joined the RAF in 1928 but his maverick streak was already evident. It proved to be his undoing three years later when, despite prior warning not to perform acrobatics below 500 feet, his wing-tip clipped the ground and he crashed.

He was pulled from the wreckage and surgeons were obliged to amputate one leg above the knee and the other below. Bader’s only reference to the crash in his log book was a typically understated: ‘crashed slow-rolling near ground. Bad show.’

His tenacious personality helped on the long and painful road to recovery and, with the aid of artificial legs, he learnt to drive a modified car, play golf and dance. He even learned to fly again but was invalided out of the RAF.

It would, in all probability, have been the last anyone heard of Douglas Bader but fate had one more card to play as the storm clouds of war gathered over Europe.

The 29-year-old saw repeated requests to rejoin the RAF turned down until it finally relented in its desperation to find pilots. He passed his refresher course turning his bi-plane upside down at 600 feet in defiance of the powers-that-be.

Bader refused to be defined by his disability but it gave him the unexpected advantage of being able to cope with the de-habilitating effect of g-force when blood rushed to the lower limbs momentarily disorientating some pilots.

His tenacity and courage was recognised by both sides and, when he was shot down and captured over France, the Germans agreed a prosthetic leg could be air-dropped to replace the one he lost in the crash.

His captors where less pleased with the pilot’s less-than-gentlemanly decision to bomb a number of targets on the way home.

If the Germans thought having Britain’s most famous fighter pilot in the bag was an end to their troubles they were mistaken.

Bader made several escape attempts and his captors, in exasperation threatened to take away his artificial legs. He was eventually sent to Colditz which housed the most troublesome prisoners of war.

It was here that he met one of his counterparts and later, life-long friend, the German fighter ace Adolf Galland,

The two men had a mutual respect for one another although it didn’t stop Bader later entering a roomful of ex-Luftwaffe pilots and loudly exclaiming: ‘My God, I had no idea we left so many of you bastards alive.’

Bader was a brash larger-than-life character whose main criticism of his big screen persona played by actor Kenneth More was that he was too polite and never swore.

The war gave Bader the chance to burn brightly on the world stage and he dedicated his post-war years with equal passion to helping the less fortunate and disabled. He was knighted in 1976 for services to the disabled.

He never treated his disability as an excuse not to be as good as the next person and that was a message he instilled in the many amputees he met and inspired.

A colleague later recalled that if Bader could have attended his own memorial service in 1982 he would have stomped over to his old friend Galland slapped him on the back and bellowed: ‘Bloody good show, glad you could come.’

St Mary’s Hospital, which is now part of St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust, honoured his memory when it renamed its amputee service the Douglas Bader Rehabilitation Centre.

The centre today helps more than 1,600 amputees a year come to terms with losing a limb through accident or illness.